Often the time and energy and money required to produce a book is under-appreciated. The average reader imagines a scene in which the lonely writer sits atop a far-away mountain, banging away at the keyboard. The writer is often blocked by some outside force, until a flash of inspiration occurs and viola, a masterpiece! And thus the reader holds the masterpiece in their hands, quietly devouring the inked pages.

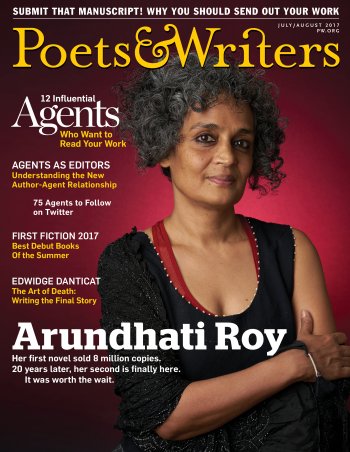

What is rarely discussed in reader circles, and even in writer circles, is the other half of the puzzle. The multitudes of people and teams that also had a hand in the work, and with whom without, that masterpiece of a book would never have reached the readers. The blood, sweat, and tears that have been shed in the process. In this modern climate of self-publishing and DIY attitudes, people often ask: what is the point of a publisher? Or an agent? Or even, an editor?

This questioning haunts me as a literary agent. I see many writers on forums talk about agents as if we are lowly serpents trolling on the talents of writer. They spew venom about the fat-cat editors in New York (whose salary is probably barely above minimum wage). It’s frustrating as no one would ask that in film. No one would ask why a script needs set-designers, or directors, or producers. As a once self-published author I fully support the advent of a new publishing paradigm. But I do believe it is important to acknowledge the amount of work that it takes to produce a beautiful book whichever publishing path one chooses to take.

Believe it or not, most of us are in this industry because we love books.

Everyone in the literary world, from publishers, agents, editors, designers, and writers are all working toward the same goal; to produce a good book. No, to produce a great book. A book that shines on the shelf, calls out to potential readers. A book that captures you with its first sentence, whose story draws you in, and whose plot keeps you up all night reading. A book that makes you excited, anxious, and sad as the amount of pages left gets slimmer and slimmer. A book that makes you sigh with satisfaction with its last sentence. A great book.

The writer spends late nights and early mornings to create a story out of thousands of words. They edit those words for months. Their beta-readers critique it, each comment a stab to the heart, but the writer bravely endures and edits it again, and again, and again. Then months to years later, when they have what they believe to be a finished project, they send it out to the terrifying gatekeepers, the agents.

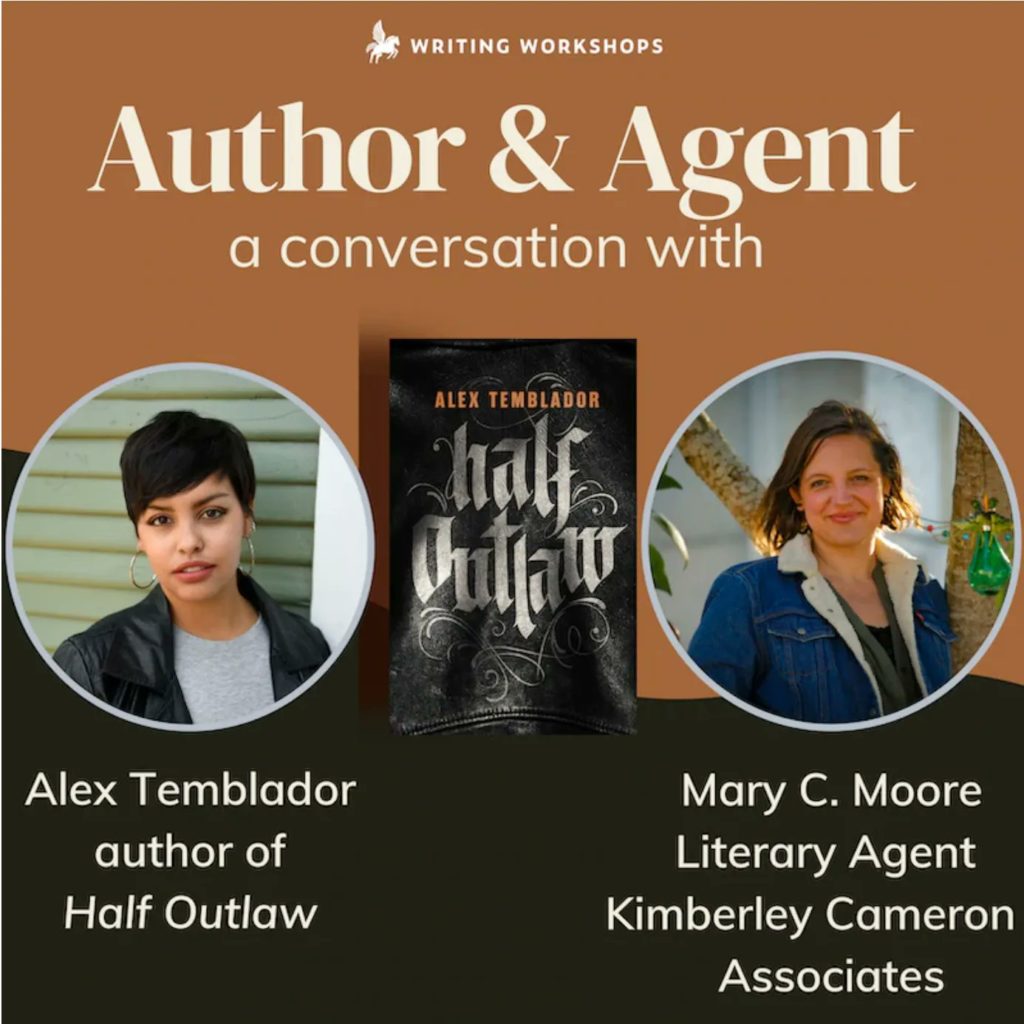

The agents read hundreds of email queries, tens of writing samples, 2-5 manuscripts a week. They endure angry authors-rejected suitors and demanding writers whom feel they deserve the agent’s time over all else. They read through the slush of manuscripts, the wanna-be bestsellers, the overwritten literary prose, the un-edited sloppy writing to find that gleam, that rough gem that catches their attention. They find out if the gem is available, comb through it and ask for edits. They edit the second draft, and the third, and the fourth. Finally they take the gem, which now sparkles, and send it out to the impossible judges, the editors. Editors with whom they have spent time developing relationships with, learning their likes and dislikes, so that one day when the right ms for the right editor comes along, they know exactly who to send it to.

The editors slough through the agent queries, requesting too many manuscripts. Their desks are piled with submissions, with current manuscripts, and with books they need to read. They read and read and read. They find a book they want to sign, fight over it with other editors, capture it for their own. They deal with demands of their bosses, marketing and sales, overbearing agents, and with stubborn, pretentious, or diva authors. They work under deadline from the publisher, the pressure always on. They edit, and edit, and edit some more. Finally it is ready to go to design production.

The designer keeps an eye on every book that gets released, they keep tabs on design trends, they know if Lucinda Grande has gone out of style and that vertical stripes are serious but horizontal are playful. They read the manuscript and have a brilliant concept for the cover. They create a first proof of the cover. They love the cover. The next time they look at it, they hate it. They redesign the font, change the image, adjust the hues. They tweak something a centimeter to the left, something else a half inch up. That one shape should be circular. And blue. No, cobalt blue. They create something beautiful. The author wants something else, the agent doesn’t like it, the editor thinks it’s okay, the publisher doesn’t care. They tweak it some more. This time it is perfect.

The publisher gathers the items needed to publish the book. The ISBN number, the Library of Congress data, the copyright, the price, the mega data, the whole sale price, the royalties, the contracts, the marketing copy, the distribution, the costs of production, the marketing and promotion. They work with book buyers, librarians, bloggers, reviewers, trade publications, newspapers, and book stores to get the final book in front of eyes, on the digital or physical bookshelf. The final push so the book is out there, a book that shines, a book that calls out to potential readers.

And all of these people take a deep collective breath and hope that they have given the potential buyer something special.

A great book.

Franklin goes on to express why submitting is so important. It’s a part of the necessary evolution and development of your writing. You need your dreams crushed so you can pick them up again and make them stronger. Ignorance is bliss, but it won’t get you published (in most cases).

Franklin goes on to express why submitting is so important. It’s a part of the necessary evolution and development of your writing. You need your dreams crushed so you can pick them up again and make them stronger. Ignorance is bliss, but it won’t get you published (in most cases).