It’s harder than ever for debut books to break into traditional publishing. The struggle is real. And it prompts authors to seek out any and every avenue that will boost their chances. Conferences, webinars, classes, critique partners are all in a writer’s potential arsenal. One of the biggest weapons, and the most dangerous, is the freelance editor. “Will hiring an editor make a difference, and if we did should we mention it in the query?” is a question often posed to agents; which is difficult for us to answer on the spot. One because there are different types of editorial and we aren’t sure what your manuscript needs:

- Developmental? An examination of the overall structure/plot/characters/pace etc. Helps a writer find plot holes, fill out flat characters, remove unnecessary tangents, and ensure the story arc is complete. This is the most common type of editorial that agents already do, but if there’s more than a few of these types of issues, it will be rejected.

- Copy-editing? An examination of the structure of the prose itself. Helps a writer enhance their prose line by line, streamlining sentences and fleshing out the narrative. If a submission desperately needs this, an agent will pass (unless the project is something they are very specifically seeking or it’s nonfiction). All manuscripts will go through a copy-editing phase before publication, but a basic sound narrative should already be there when submitting.

- Proofreading? An examination of grammar and spelling. Helps a writer catch any grammatical or spelling errors. This is the last edit on a manuscript and the first issue noticed by a reader. An agent will not take on a manuscript littered with errors, as they would have to spend valuable time correcting them before submitting it to editors.

Two because, with the internet, the self-publishing revolution, and the economic recession that squeezed the traditional houses, there has been an explosion of freelance editors hanging out their shingle and not all are right for your work. We don’t want to be the one to tell you that you may have wasted your money (if a traditional deal is your goal).

If the author decides to hire an editor, they should tread lightly and do their research.

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.

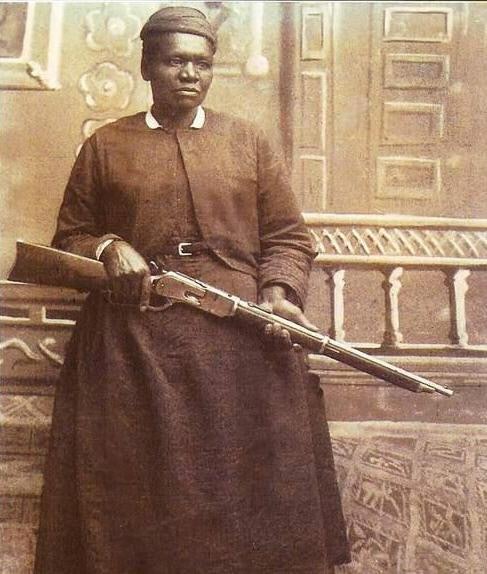

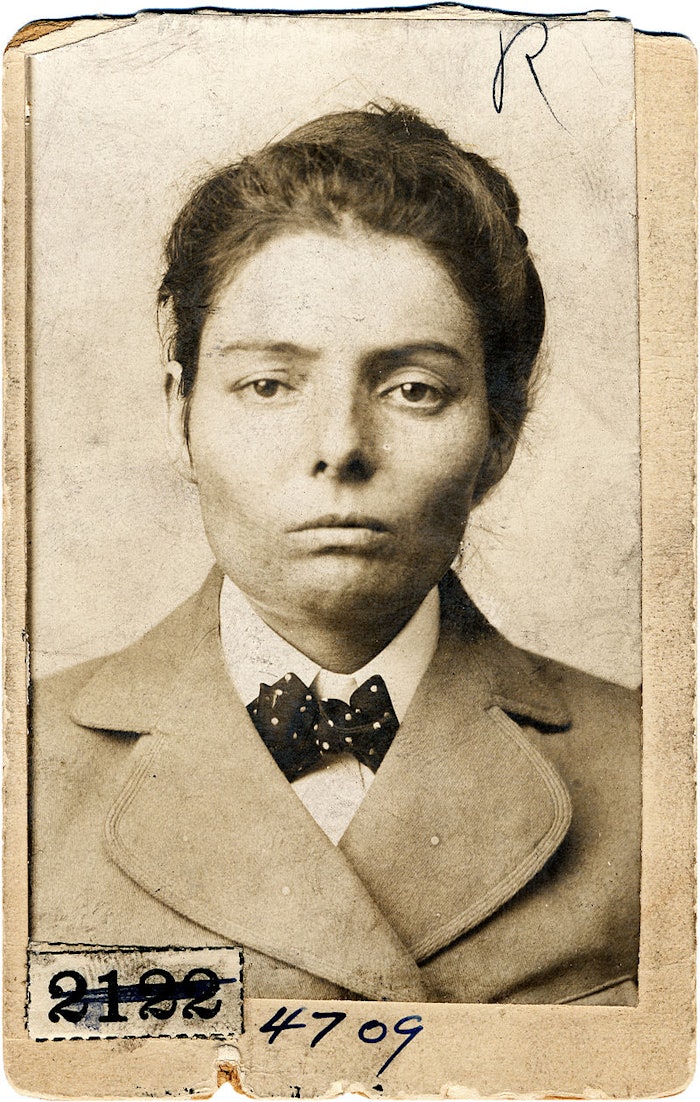

Although the movie that inspired this title has some gorgeous cinematography, stellar story arc, and an awesome theme song, due to its casual racism and utter lack of female characters, here the Good, Bad, and Ugly have been replaced by real-life badass female wild westerners.*

The Good. Mary Fields, often called “Stagecoach Mary,” was born into slavery around 1832, and after being emancipated at the age of 30, made her way west to Montana. Fields, who was very tall and extremely strong, worked as a general handyman and laborer at a school for Native American girls. She had a reputation for being strong, blunt, and more than willing to get in fights with people who annoyed her. At one point the local medical examiner claimed, she had “broken more noses than any other person in central Montana.”

Hiring a freelance editor can absolutely help whip your manuscript into shape. With the right editor, your story will be polished until it gleams, trad-publishing-ready, thus appealing to agents. How to find these miracle workers? Look for editors who are experienced publishing professionals in your genre. They have either worked as an editor for one of the traditional houses for a few-plus years or they are a traditionally-published successful author. They may even be literary agents (but be careful, more on this under The Bad). If they do not have the prerequisite publishing experience, then they will have a resume of books that they edited which have gone on to be successfully published. These editors are costly, but they will give you the highest odds of producing a manuscript that will eventually make it to the top. Often agencies will have a list of these editors on hand that you can ask for if an agent shows interest in your work. If you work with one of these editors, then yes, definitely mention it in the query letter.

The Bad. From a young age, Laura Bullion was destined to be an outlaw. Her father was a bank robber, and while working as a prostitute in Texas she joined the Wild Bunch gang, where she ran with outlaws like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Bullion helped the gang with their robberies, and came to be known as “Rose of the Wild Bunch.” Bullion would help sell the stolen items, forge checks, and is suspected to have disguised herself as a man to help with heists.

These editors you want to avoid at all costs. They are predators eager to take advantage of the vulnerable author. If an editor solicits you and/or promises you will be published at their “house” after hiring them, it’s probably a vanity press scheme. If an agent offers to edit your manuscript, claiming they will represent you after you’ve paid them for said editing, this goes against AAR’s (Association of Authors’ Representatives) Canon of Ethics. If an agent pressures you to work with a freelance editor and is insistent on a specific company, or an editor claims they can get you signed by a specific agent, be wary.** This is an old scam in which the agent gets a kickback from sending authors to said editor and visa versa. A quick online search of any suspicious person with “scam” in the search line will usually bring up red flags right away. Also be sure to check out Writer Beware on the SFWA website. They are constantly updating publishing scams to watch out for.

The Ugly. Eleanor Dumont was called Madame Moustache because of her appearance later in life. But when she was young, she was regarded as exceedingly beautiful. Dumont first made her reputation as a gambler in San Francisco in 1849, determined to cash in on the California Gold Rush. Her casino in Nevada City was a success, and led to Dumont opening a second casino with additional games of chance. After the Gold Rush subsided, Dumont bought a ranch, but lost her fortune when she fell in love with a con man named Jack McKnight. When he sold the ranch and absconded with the proceeds, Dumont tracked him down and shot him dead.

These are the editors that are perhaps qualified to edit, but have never edited in the traditional publishing world. MFA students, other writers, English teachers, librarians, etc. fall into this category. To be clear, these are not actually ugly editors (just using the name to make it fit my oh-so-clever blog structure). They are often great proofreaders and much cheaper than The Good. Because of their lower rates, hiring them for a developmental edit over the more expensive experienced editors, is tempting. However, due to their lack of traditional publishing experience, they may not steer your manuscript in the direction someone in the industry would. These editors are more of a financial gamble, and you could be better off finding a critique partner that will do the same work in exchange for a critique from you. But you also may get lucky and stumble on someone who has a natural knack for developmental editing. If you hire one of these editors, it’s not necessary to mention this in the query.

As always, your best weapon is research. Before making a decision to partner financially with anyone in the industry, do your research to determine if they are the best option for your writing career.

*On my manuscript wish list is historical fiction about any/all of these female outlaws!

**I have recommended on occasion that an author work with a freelance editor because I really loved their story concept, but it needed too much editorial for me to take on. I also have a client who went to an editor on their own after I passed with notes, a year later the manuscript was in fantastic shape. I signed them immediately and sold the manuscript within three months.

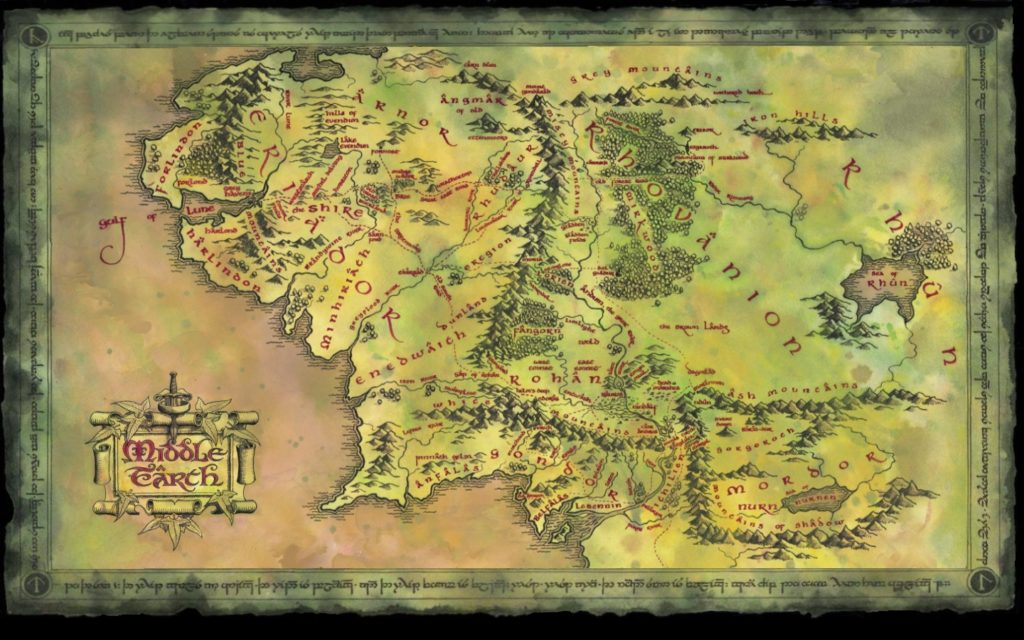

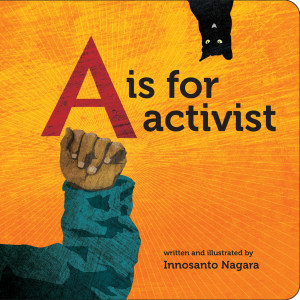

I am a cis white female married to a Mexican and within my inner circle of friends are multiple bi-racial couples (japanese, jewish, black, latino, white). I have queer friends and disabled. This isn’t something that is intentional or that gives me allowance to be smugly color-blind, it simply is a truth of my generation. We are becoming a global society. So when I start a submission that has a cast of all white cis characters, because it doesn’t reflect my reality, more often than not, I lose interest; or if the writing is really good I begin mental notes on which characters could be changed. I also lose interest when the diversity is just stereotyped personas. My friends may be multi-ethnic and of multi-sexualities, but they are not my friends because of this. They each have their own personalities unique from (although entwined) with their identities. Yes, one might be flamboyantly gay man, but he is also a doctor who has traveled the world helping impoverished villages. Another may be a black woman with some sass, but she is also an incredibly thoughtful Christian who loves Lord of the Rings and to run marathons. So when I say I am looking for a diverse cast, this is what I mean. You can still be a cis white writer and write a diverse cast with depth and truth.

I am a cis white female married to a Mexican and within my inner circle of friends are multiple bi-racial couples (japanese, jewish, black, latino, white). I have queer friends and disabled. This isn’t something that is intentional or that gives me allowance to be smugly color-blind, it simply is a truth of my generation. We are becoming a global society. So when I start a submission that has a cast of all white cis characters, because it doesn’t reflect my reality, more often than not, I lose interest; or if the writing is really good I begin mental notes on which characters could be changed. I also lose interest when the diversity is just stereotyped personas. My friends may be multi-ethnic and of multi-sexualities, but they are not my friends because of this. They each have their own personalities unique from (although entwined) with their identities. Yes, one might be flamboyantly gay man, but he is also a doctor who has traveled the world helping impoverished villages. Another may be a black woman with some sass, but she is also an incredibly thoughtful Christian who loves Lord of the Rings and to run marathons. So when I say I am looking for a diverse cast, this is what I mean. You can still be a cis white writer and write a diverse cast with depth and truth. On representing marginalized voices: If you are writing from the point of view of a marginalized person (POC, queer, disabled etc.) and part of the story development is the experience of inequality, prejudice etc., it is extremely difficult to capture the truth of the voice if you as a writer has not experienced the social injustice personally. As a literary agent, I am keenly aware that I cannot edit a manuscript with a marginalized voice without having someone with experience to show me certain ignorances I have. I know as a woman, when I see female points of view written by men that are stereotypical and offensive, I get angry, so I can only imagine the rage and betrayal someone who is further marginalized feels when their story is told by someone who has no real concept of it. If you are going to go down that path, then please please be sure that you have close friends or advisors who can speak to the experience, read your manuscript and point out the subtleties that you will misrepresent. And I guarantee you will misrepresent, despite how open-minded or educated you may believe yourself to be.

On representing marginalized voices: If you are writing from the point of view of a marginalized person (POC, queer, disabled etc.) and part of the story development is the experience of inequality, prejudice etc., it is extremely difficult to capture the truth of the voice if you as a writer has not experienced the social injustice personally. As a literary agent, I am keenly aware that I cannot edit a manuscript with a marginalized voice without having someone with experience to show me certain ignorances I have. I know as a woman, when I see female points of view written by men that are stereotypical and offensive, I get angry, so I can only imagine the rage and betrayal someone who is further marginalized feels when their story is told by someone who has no real concept of it. If you are going to go down that path, then please please be sure that you have close friends or advisors who can speak to the experience, read your manuscript and point out the subtleties that you will misrepresent. And I guarantee you will misrepresent, despite how open-minded or educated you may believe yourself to be.

At the last conference that I took pitches, near the end a flustered but determined writer sat at my table. Her first words were, “I was just told my project is unmarketable, but I’m going to pitch it anyway.” My interest was piqued, not in the project, but in what she had been told and why. I’m always curious to hear the advice given to writers by other industry professionals. Usually it tends to be something I and many others agree with. But there are cases where we disagree. This business does have a subjective element to it after all. And sometimes it’s advice that I perhaps hadn’t thought of, but would agree with. On occasion it’s something I didn’t know and would want to follow up on. And sometimes, yes, it is painfully obvious bad advice which needs to be corrected immediately. (Anyone who advises a debut author to throw up their book on Amazon to “garner feedback” before taking it to agents or publishers, I’m looking at you.)

At the last conference that I took pitches, near the end a flustered but determined writer sat at my table. Her first words were, “I was just told my project is unmarketable, but I’m going to pitch it anyway.” My interest was piqued, not in the project, but in what she had been told and why. I’m always curious to hear the advice given to writers by other industry professionals. Usually it tends to be something I and many others agree with. But there are cases where we disagree. This business does have a subjective element to it after all. And sometimes it’s advice that I perhaps hadn’t thought of, but would agree with. On occasion it’s something I didn’t know and would want to follow up on. And sometimes, yes, it is painfully obvious bad advice which needs to be corrected immediately. (Anyone who advises a debut author to throw up their book on Amazon to “garner feedback” before taking it to agents or publishers, I’m looking at you.)